This summer I attended two very different conferences in my field, where I gave two inter-related papers reflecting on the processes of scholarship in a digital world.

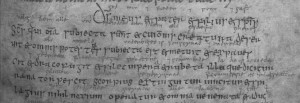

The first confer ence, in Cambridge, was a small one of specialists in early English history, Writing Britain, 500-1500. My paper, “Inscribing Identity: Northumbrian Old English and Latin in Dialogue,” addressed two of the conference themes: the role of language in regional identity and digital humanities. In it, I explored some theories about extensive versus intensive social power as a way of understanding the political dynamics in tenth century (Viking era) northern England, using the bilingual text (Latin glossed with Old English) from my current project on the manuscript known as Durham Cathedral Library A.IV.19 (one set of texts already published available on ScholarSpace).

ence, in Cambridge, was a small one of specialists in early English history, Writing Britain, 500-1500. My paper, “Inscribing Identity: Northumbrian Old English and Latin in Dialogue,” addressed two of the conference themes: the role of language in regional identity and digital humanities. In it, I explored some theories about extensive versus intensive social power as a way of understanding the political dynamics in tenth century (Viking era) northern England, using the bilingual text (Latin glossed with Old English) from my current project on the manuscript known as Durham Cathedral Library A.IV.19 (one set of texts already published available on ScholarSpace).

That brings me to the digital part, where I got to show off the work of colleague David Goldberg , collaborating with me in producing a tool to digitize a glossed manuscript. The problem with typing up a glossed manuscript is how to represent the relationship between the base word (Latin in this case) and the Old English gloss word floating above it. MS Word has the advantage of needed special characters and other formatting, but has no way to tie the two words together other than hard or soft spacing, which often gets skewed.

, collaborating with me in producing a tool to digitize a glossed manuscript. The problem with typing up a glossed manuscript is how to represent the relationship between the base word (Latin in this case) and the Old English gloss word floating above it. MS Word has the advantage of needed special characters and other formatting, but has no way to tie the two words together other than hard or soft spacing, which often gets skewed.

David wrote a program we are calling Glossa, still in its infancy, that allows me to type or paste in the two lines of text, “grab” the Latin word, then grab the Old English gloss word(s), creating a permanent association. This means we can create a two-way glossary (Latin to Old English or vice versa), allowing further linguistic analysis as well as searchability of the text. Finally, this xml code can be shared with the Text Encoding Initiative for others to use. Attendees at the Writing Britain conference were very interested in both the potential for the software as well as the linguistic implications of analyzing this bilingual text for what it can tell us about tenth century England’s diverse political and social landscape.

The other conference I attended was the International Medieval Congress in Leeds, with over 2000 delegates. My paper there may seem antithetical to the digital world, given in a series session called “Slow Scholarship.” However, the aim of the sessions was not to dismiss the benefits of “big data” with digitization, but to combine it with the kind of patient, focused attention to detail that humanities research has always prized. Digitization should free us up to spend more time contemplating the meaning of texts and artifacts, not zoom us past that stage of reflection.

My paper, “Letter by Letter: Manuscript Transcription and Historical Imagination,” explored the theory of “deep attention” in relation to “hyper attention” as developed by Kate Hayles. One slow side of my work is transcribing, letter by letter, the glossed manuscript. In doing so, I see things--odd words and different understandings the glossator has of the text–that I would not have noticed if I had just scanned it and then searched the text. On the other hand, I want that tedious work of typing to have some long term value, hence my desire to digitize it in such a way that it is searchable and can be compiled to look for patterns that I might not see in the slow process of transcription.

The other slow bit in my title has to do with imagination, and here I transgress the boundaries of traditional historical scholarship by writing historical fiction (or attempting to). The more time I spent with this glossator–whose name is Aldred–the more I got to know him, in a peculiar way, given that the only evidence we have about him is from his Old English gloss translations of Latin liturgical and encyclopedic materials and two “colophons” where he describes himself somewhat ambiguously. But to know him in his home terrain means exploring the landscape he inhabited.

So off I go to England to traipse around Northumbria and Cumbria, imagining what he might have seen a thousand years ago, and taking some (digital!) pictures to remind me. This one to the right, at Bakewell in the Peak District, shows one side of a cross fragment with a carving of the Scandinavian hero/god Woden on his horse Sleipnir, an image illustrating the Viking settlement and acculturation to Christianity in tenth-century England (given comments below, I am now revising this view, especially since the cross fragment is dated by some to eighth or ninth century).

Meanwhile, this image of stone fragments, also at the church in Bakewell, is a reminder of our fragmentary knowledge of the past, similar to the fragments left by Aldred in the manuscripts he glossed. It is my job to take these jigsaw pieces and built a puzzle from them. That takes time, time digital tools can enhance.

Meanwhile, this image of stone fragments, also at the church in Bakewell, is a reminder of our fragmentary knowledge of the past, similar to the fragments left by Aldred in the manuscripts he glossed. It is my job to take these jigsaw pieces and built a puzzle from them. That takes time, time digital tools can enhance.

I loved the ‘Slow Scholarship’ session, and your paper especially. It was lovely to see you. I’m intrigued by your reading of the Bakewell rider as ‘Woden on Sleipnir’ – is that something you can go into in a bit more detail?

By: Victoria (Thompson) Whitworth on July 22, 2014

at 10:32 pm

Good question.

Joyce and I were mystified by the cross with a horse and (mostly missing) horseman at the top. Inside the church we found signage offering a “possible interpretation” for the “pagan panels” and the “Christian panels,” labels which we found dubious. The Woden and Sleipnir is posited from the eight legged horse, so we duly went back outside to reexamine said horse in person. I could go either way–a regular horse or not. It could be a bit like that horseman on the Chester-le-Street fragment identified as Eadmund.

The panel signage also identified the critter below the horseman as the squirrel Ratatosk, but I wouldn’t know him if he came up and bit me!

I don’t find the cross in Bailey’s Viking Age Sculpture, but there is an archaeological report online from a 2012 excavation that refers to controversy over the interpretation (http://www.archaeologicalresearchservices.com/Bakewell%20High%20Cross%20-%20Report%20on%20an%20Archaeological%20Excavation.pdf see section 4.1).

Do you have a better interpretation?

By: kljolly on July 23, 2014

at 11:06 am

Re: no way to tie the two words together…

In MS Word, I use a 2 row table per line, one column per ‘word’, using alignment within a cell (left, centre or right) to show the position of the gloss in relation to the original Latin. When finished copying text and gloss, I make the table invisible to the reader using the ‘no border’ function.

By: Seumas MacRath on July 28, 2014

at 9:16 pm

Thanks! I have never gotten comfortable with Word’s table function, but this seems like an easy way to at least set up my transcription. Of course, it doesn’t allow for the linking that the programmer and I are working on, to create a two-way glossary.

By: kljolly on July 29, 2014

at 10:09 am

I think the chances of it being Woden on Sleipnir are vanishingly small. As far as I know the only two images of Sleipnir are those on the Gotland picture stones, Tjängvide and Ardre VIII, which are from the same template and may be as late as the tenth century, according to Lisbeth Imer. Given the number of riders in Insular sculpture of the ninth and tenth centuries, I see no need to introduce a Scandinavian myth where there is no other good evidence. Other than at Gosforth I think the case for Scandinavian pagan iconography on Anglo-Saxon sculpture has been hugely overstated.

By: Victoria (Thompson) Whitworth on July 30, 2014

at 10:07 pm

I am so glad you said that about the prevalence of “pagan” iconography being scant. The identification of pagan motifs seem so smack of the 19th century “Search for Anglo-Saxon Paganism” (thanks, Eric Stanley for that!) in charms, etc that I have fought against.

So we could have Scandinavian motifs and styles but without all of the angst about pagan versus Christian.

By: kljolly on July 31, 2014

at 11:43 am

Absolutely. In many ways the scholarship is still stuck in the late Victorian desire for heroic Vikings which Andrew Wawn dissects so beautifully.

By: Victoria (Thompson) Whitworth on August 8, 2014

at 10:06 pm

[…] was viewing Anglo-Saxon stone monuments. I already posted on a few at Heversham and Heysham at at Bakewell. We also stopped at Sandbach, Eyam, and Wirksworth, the first site an expected known one and the […]

By: Stone | Revealing Words on August 1, 2014

at 3:19 pm

[…] [cross posted from Revealing Words] […]

By: Karen Jolly’s Slow Scholarship – Digital Arts and Humanities on October 9, 2018

at 11:47 am