It has been almost a year since my last post, a year dedicated to another project I will hopefully blog about soon (“Medieval Worlds: Muddling through the Middle Ages”). Aldred feels neglected, perhaps, but is not far from my thoughts even if those are not committed to writing in his fictional story.

In the meantime, here I sit in Leeds waiting for the start of the International Medieval Congress, emulating Johnathan Jarrett’s A Corner of Tenth Century Europe by posting something from way back that has never seen the light of day but to which I keep returning to pull ideas.

This piece comes from 2011, so more than a decade ago, and shows my nascent thoughts about bringing into conversation my early medieval research on Britain with my location in Oceania. I gave it or parts of it as oral presentations and submitted versions to journals, but the peer reviews rightly pointed out areas that needed work, after which it languished on a back shelf while I moved on to other endeavors.

Nonetheless, I find myself invoking bits of it in my current work, including the panel presentation for IONA here at Leeds on Tuesday. Its presence here, warts and all, may serve as a backstop in case anyone wants to know more about the main characters.

Before you read on, please note three caveats about this mostly unrevised and lightly edited paper:

- This was researched and written in 2010-11 and has not been updated with more recent work on the subjects, including my own work on Aldred and new approaches to studying early medieval Britain. As a consequence, I am omitting from the essay the now well out of date historiographic overview, and have added a few but not all more current references in footnotes with “see now.”

- The journal peer reviewers made some cogent observations that have not been addressed (thank you to the readers and my apologies for not following through). This includes the overblown rhetoric about the medieval-modern divide, about which I have written elsewhere on this blog, and the uncomfortable switching between the two protagonists.

- I am a settler scholar in Hawai‘i but not a researcher in Pacific Islands studies. Rather, I am a Euromedievalist turned global medievalist, with an ear listening to Indigenous voices in Hawai‘i and in the field of early medieval English studies.

Finally, I should note that my blog title with the question mark echoes the review essay by Neil Price and John Ljungkvist,“Polynesians of the Atlantic? Precedents, potentials, and pitfalls in Oceanic analogies of the Vikings,” Danish Journal of Archaeology (30 July 2018), which offers a more current and insightful critique of the problems of comparative histories.

Vikings of the Pacific: An Oceanic View of the Early Medieval British Isles

May the letter, faithful servant of speech, reveal me.

Salute all my brothers with your kindly voice.[i]

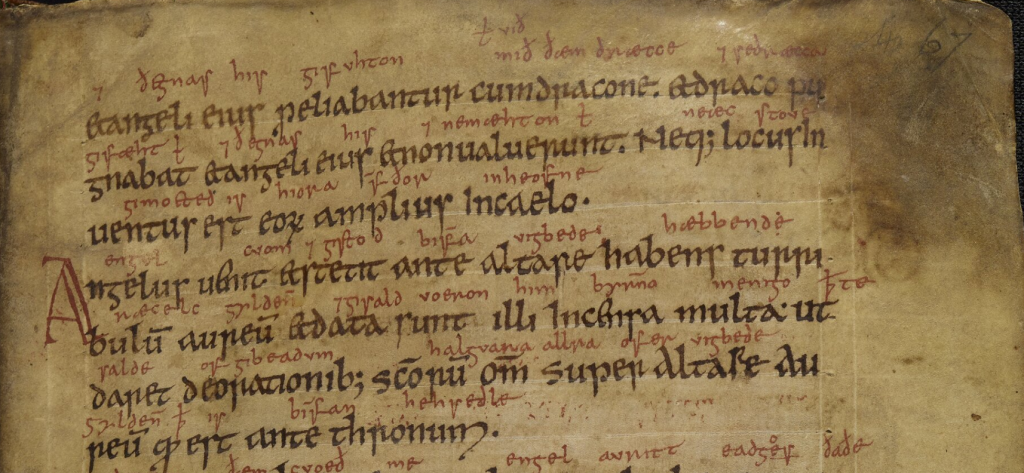

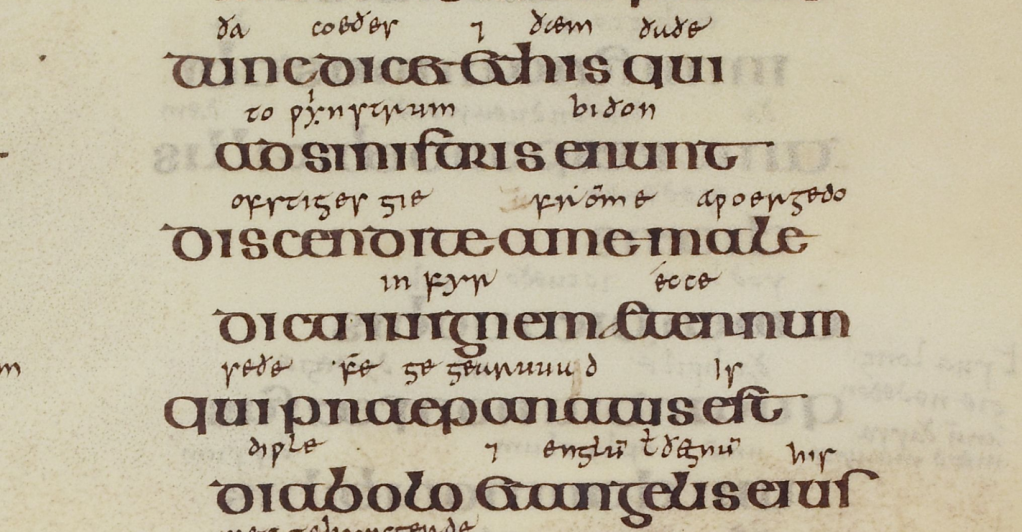

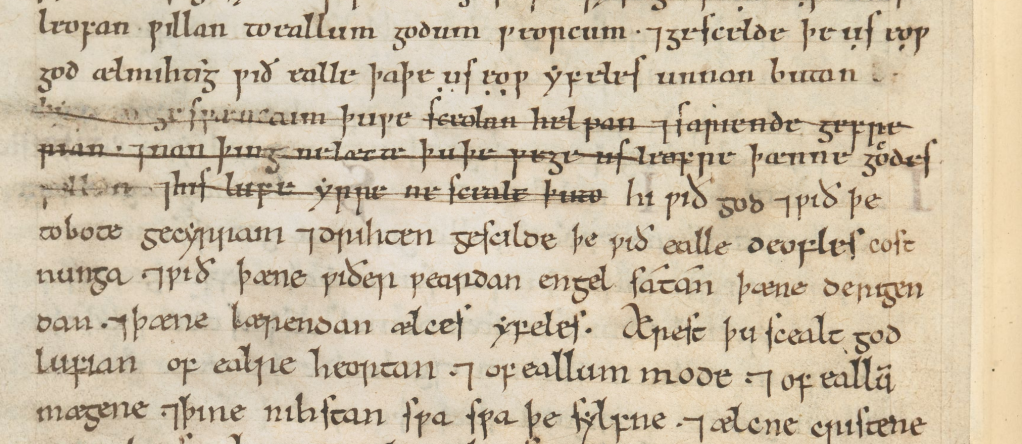

Sometime in the middle of the tenth century, a Northumbrian priest named Aldred penned these lines as part of an extended, and quite self-revealing, colophon he wrote in the Lindisfarne Gospels manuscript, a treasured relic at the community of St. Cuthbert at Chester-le-Street, slightly north of present day Durham in Northumbria. Aldred had just finished glossing in Old English the Latin text of the four gospels and now with a considerable flourish, he memorialized his handiwork by adding himself to the list of illustrious original designers of this eighth-century gloriously decorated manuscript. His enhancement—bringing the Northumbrian dialect of Old English into dialogue with the Christian language of Latin—places him as a translator and mediator between local and global. Accordingly, the colophon is also bilingual, alternating between Latin and Old English in a way that reveals Aldred’s cultural hybridity as well as unique view of Viking-era English Christianity.

The old net is laid aside;

A new net goes afishing.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, a Maori-Irish doctor from New Zealand closed his masterful account of Polynesian societies, Vikings of the Pacific, with an epilogue quoting this Maori proverb and offering a poignant query: “The old net is full of holes, its meshes have rotted, and it has been laid aside. What new net goes afishing?”[ii] For Te Rangi Hiroa, Sir Peter Buck, “the glory of the Stone Age has departed out of Polynesia,” its “regalia and symbols of spiritual and temporal power…scattered among the museums of other people,” including the one where he served as director, Bishop Museum in Honolulu. Hiroa/Buck was uniquely positioned by his dual heritages and education to bring into dialogue old and new worlds in collision.

Both Aldred the priest and Te Rangi Hiroa speak in quite personal terms about the academic work they performed. Each stands at a temporal, geographic, and cultural nexus, but seemingly unrelated to one another except through the accident of a title, Vikings of the Pacific, that attracted the attention of a contemporary historian of [early medieval Britain] working in Honolulu. It is highly unlikely that anyone other than the author of this essay would have connected these two historical figures or would make this comparison. The voice adopted in this essay is therefore autoethnographic: the juxtaposition of two unrelated historical figures is made possible by exposing the traditionally invisible position of the historian as outsider and mediator, who joins them as the third point in a triangular interpersonal and atemporal relationship.[iii] Consequently, this article offers a unique mediation between disparate worlds—medieval and modern, pre-and post-contact, English and Polynesian—and of necessity begins with an explanation of this conjunction and ends with its potential meaning for the role of the historian.

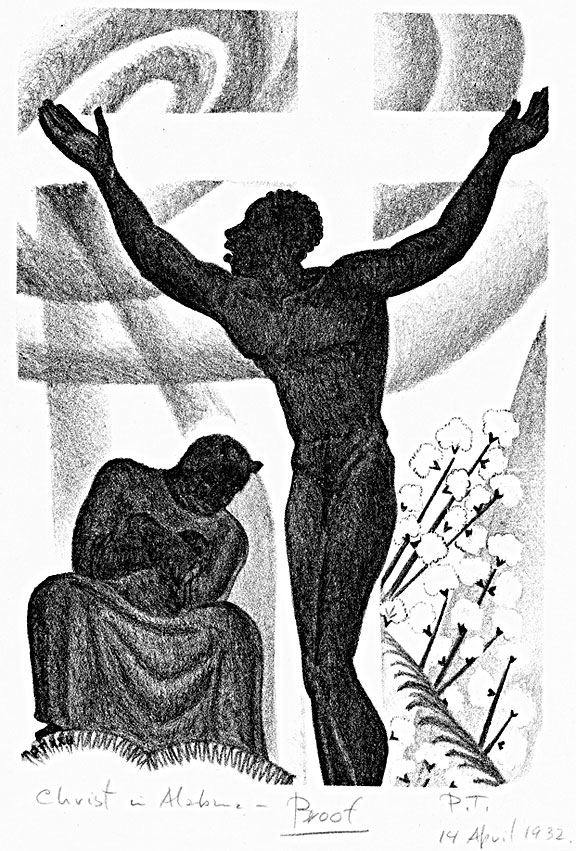

As a medieval European historian in the middle of the Pacific, my research is often seen as arcane both here and in England, where I am often asked, “why would someone in Hawai‘i be studying Anglo-Saxon society?” My answer, depending on the interlocutor, is sometimes “as an anthropologist, studying the natives,” turning the tables as it were. And yet there is a deeper issue imbedded in the question and my answer: in Hawai‘i, I have learned new ways of seeing medieval Europe through the lens of world history and comparisons to Pacific historiographies. Deliberately making this comparison between pre-modern England and the contemporary Pacific calls into question the way that Oceanic cultures have been “medievalized” by a colonizing modernity that created this temporal landscape of historical evolution. Reversing perspectives to give a Pacific view of the British Isles in the early Middle Ages is one way of undoing this process, in contrast to the more usual vice-versa of European history as the measure of civilizational “progress.”

Nonetheless, the comparison remains dangerous in the sense that it suggests, given the lingering nature of the modern narrative of progress, that Pacific cultures were in some cases “pre-historic” or in other ways “medieval,” with all of the baggage those labels imply.[iv] For example, the human history of Hawai‘i includes some generic similarities to the early medieval British Isles, including waves of migration, local territories defined by diverse ecosystems (valley cultures running from the wooded highlands down to the sea known as ahupua‘a), a long period of separate island governance, and eventual unification of the islands under one dominant military leader, Kamehameha the Great, all prior to the cataclysmic events of modernity—catastrophic depopulation and cultural genocide—precipitated by European and American colonial ventures, up to and including the imposition of this historical narrative of progress toward unification and centralization.[v] Such colonial narratives of the Pacific often rely on a limited number of historical voices in what M. Puakea Nogelmeir has labeled “a discourse of sufficiency” that ignores Hawaiian language sources.[vi] Resistance to, as well as negotiation with, that western colonial narrative is widespread in the Pacific. For example, Linda Tuhiwai Smith in pointing out how “research” has been a western colonizing project calls into question aspects of western historiography, such as the tendency toward temporal binaries and the colonial trap of modernity.[vii] These and other postcolonial voices from the Pacific supply grounds for querying the colonial-era medievalization of earlier European history.

Thus the broader aim of this essay is to highlight the instability of the term medieval in relation to its analogue, modern, but from a Pacific Islands view. This Oceanic perspective not only can help reimagine the medievalized European past but also offer a new way of doing history free of some of the invisible constraints imposed by modernity. [….] From its European intellectual inception, modernity of necessity imagined a medieval past reduced to a static condition of “not modern” that can occur subsequently in any time or place. By its very name, post-modernism has not escaped this paradigm; its deconstruction of modernity as progress neither marks a return to the medieval nor offers a way to reconceptualize these temporal divides. Carol Symes in her essay surveyed the problematic medieval and asks a question echoing Te Rangi Hiroa’s what new net goes afishing: “What new historical paradigms could we develop?”[viii] This essay offers some possible answers by triangulating between the historian, her object of study in tenth-century Northumbria, and a Pacific sense of place found in her academic home. In particular, this essay challenges modern assumptions about secularity in the academy by analyzing the hybrid voices of cultural translators, Aldred, Hiroa/Buck, and the author as historian.

The first part of this essay, “Post Mortem on Modernity,” exposes this problematic historiographical landscape in order to pursue a geographic and temporal reorientation, but is here edited out except for the conclusion. The second section, somewhat redacted, examines a medieval case study, the Northumbrian world of the Venerable Bede’s tenth-century heirs at the community of St. Cuthbert, specifically Aldred’s expression of an Englishness marginalized by the Viking disruptions and the rise of West Saxon linguistic and political hegemony. Pacific historians’ negotiations between pre- and post-contact eras offer other ways of telling the story of this cultural disruption and continuity across cultural divides. The third section then analyzes ways of doing history from a transoceanic perspective through the eyes of Maori-Irish ethnographer Te Rangi Hiroa (Sir Peter Buck), and his articulation of Polynesian identity in Vikings of the Pacific. The conclusion returns to the autoethnographic in search of historiographic implications.

Post Mortem on Modernity

[…]

The combined colonial legacy of secularism and ethnic nationalism leaves us with a lingering historiographical bias toward political centralization and expansion, such that we remain insensitive to other, more diffuse and shifting notions of power and hybrid identities. Traditional accounts of Anglo-Saxon England, assuming this vision of progress moving toward singularity and unity, usually trace the seemingly inevitable rise of Wessex, symbolized in the turn around victory of King Alfred the Great over the Viking Guthrum.[ix] For similar reasons, King Kamehameha the Great is lauded by many modern historians for uniting the Hawaiian islands right on the cusp of western colonial contact, and his heirs, like King Alfred’s, followed the Great King’s lead in the consolidation and centralization of military, political, economic, and legal control of lands and human resources that modernity marks as progress.[x] In particular, modern secularization makes us blind to spiritual power, an incommensurability particularly hard to address in the secular academy and one with which Pacific historians regularly struggle.[xi] And yet it is precisely the spiritual authority and physical location of a dead saint that wields considerable power in the English community imagined by Aldred and his peers in the late tenth century.

The Community of St. Cuthbert: Bede’s Tenth-Century Heirs

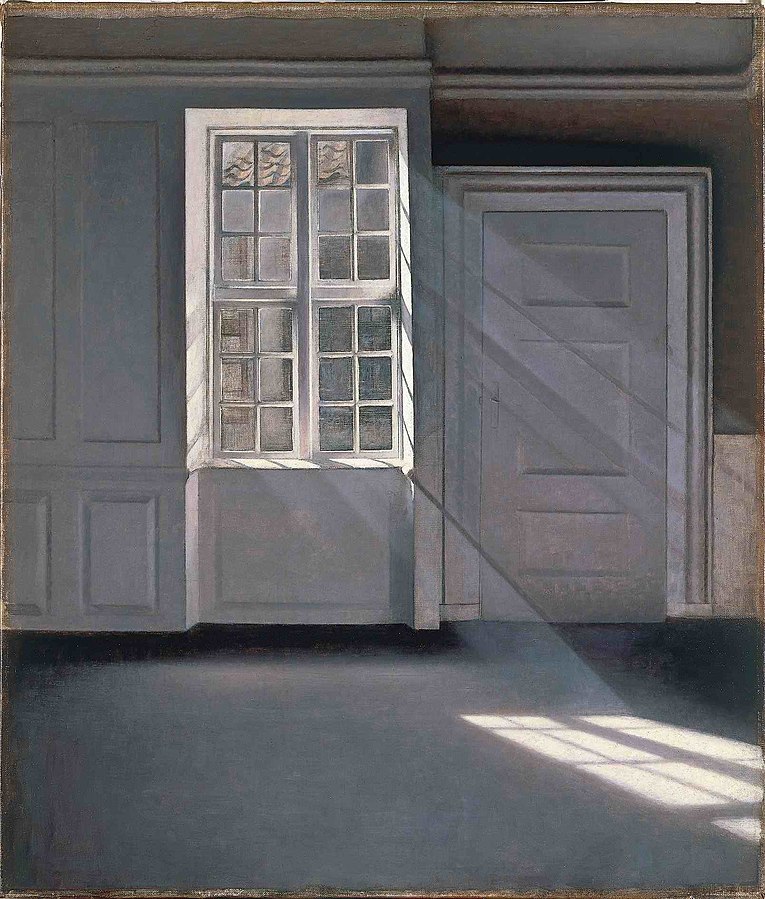

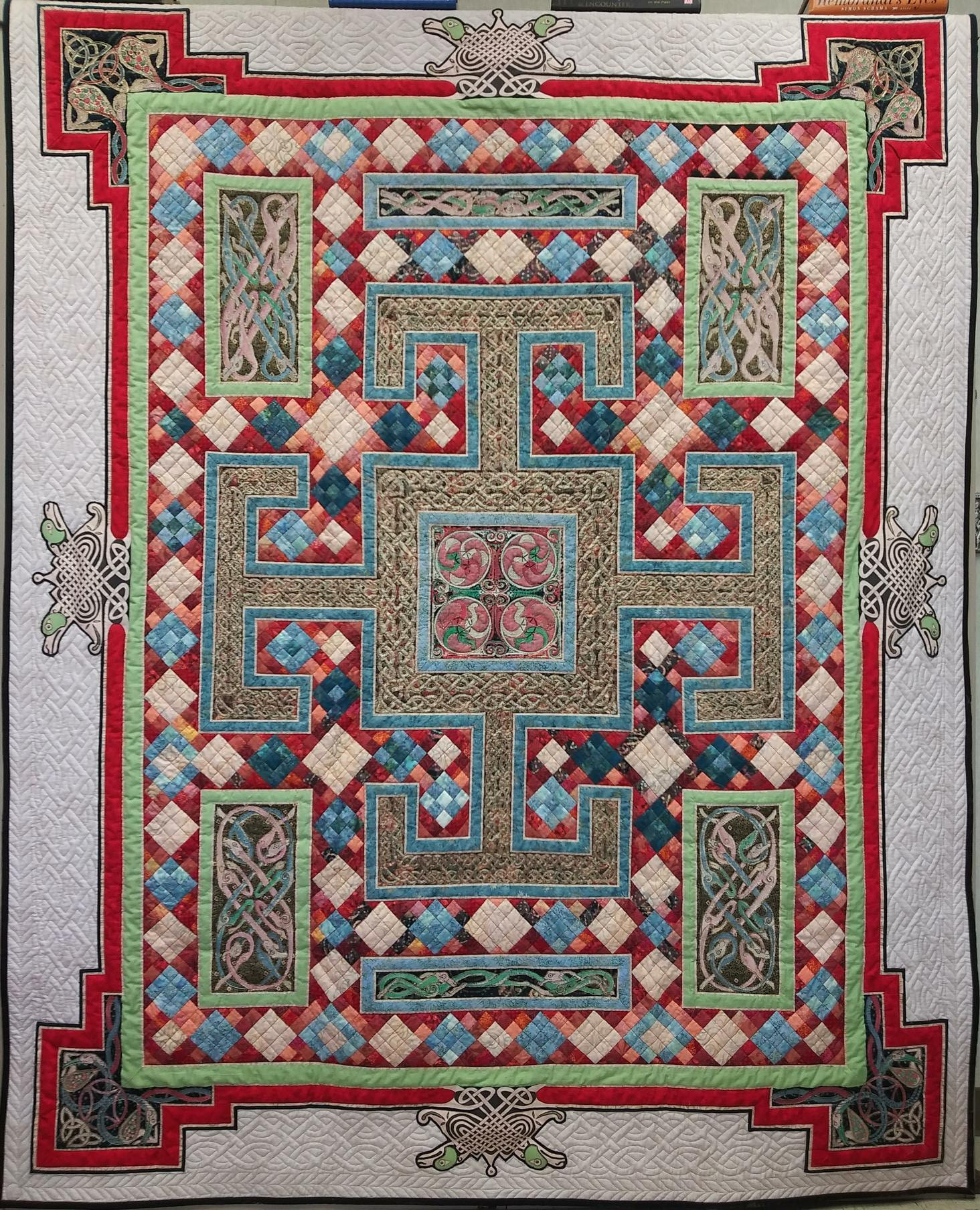

The lands north of the Humber river stretching beyond Hadrian’s wall to Scotland retain a distinctive heritage and identity to this day, intertwined with the long course of “English” history. Northumbria in the early medieval era (c. 600-1100) is nonetheless marked by a rise and fall trajectory in relation to the master narrative of Anglo-Saxon history. Its heyday in terms of contributing to English history was in the eighth century, the so-called golden age of Northumbria, with its hybrid Irish-English legacy, highlighted in the brilliant artistic achievements of the monastic community of Lindisfarne and its satellites still visible in sculpture and manuscript illumination as well as memorialized in the Venerable Bede’s ecclesiastical history of the English people.[xii] Arguably the most celebrated English artifact of eighth-century Northumbria besides Bede and his work is the Lindisfarne Gospels manuscript with its colorful carpet pages and evangelist portraits, prominently on display in the British Library in London.[xiii] Both Bede and the Lindisfarne Gospels serve as exemplars defining “Englishness,” but both have this eighth-century Northumbrian heritage embedded in them that was appropriated after the golden age by south of the Humber West Saxon royals who sought legitimacy for their political hegemony in the spiritual legacy of Lindisfarne, symbolized by its most famous saint, Cuthbert. Indeed, the living presence of Cuthbert presides over this whole history in ways nearly invisible to modern secular eyes.

In contrast to its glory days and the rising power of Wessex, the late ninth and tenth-century history of Northumbria is marred by a fragmented political landscape of competing bands of Vikings and local elites. In this narrative, the beleaguered Lindisfarne religious community abandoned its famous tidewater location, carrying their relics and treasures with them to one of their lesser estates at Chester-le-Street, where they held on through the turmoil for a century, rescued ultimately by the patronage of the West Saxon monarchs and monastic reform after the community’s move to a new site at Durham in the eleventh century.[xiv] Meanwhile, translated from Latin into the West Saxon dialect of Old English, Bede’s history became the foundation for a vernacular English historical tradition sponsored by King Alfred (r. 871-899).[xv] To Chester-le-Street came his heirs, Wessex Kings Athelstan in 934 and Edmund in 945, seeking to honor Saint Cuthbert with gifts and gain his approval, while back home in the south they enhanced the liturgy celebrating this Northumbrian English saint.[xvi] By the tenth century, then, Northumbria’s value lay in its past.

The deadest of the dead zone in the histories of this period in Northumbria occurs in the second half of the tenth century, precisely when Aldred lived and worked on the Lindisfarne Gospels and other manuscripts at the Chester-le-Street community of St. Cuthbert. Even the local histories preserved at Durham have little to say about the community’s activities and scant artifactual evidence survives—certainly nothing like the eighth-century Lindisfarne treasures they preserved—except the odd handiwork of Aldred and his fellow scribes.[xvii] Consequently, Aldred sticks out as a lonely figure in a dreary time. Yet he may have seem himself and his community’s history a bit differently, given that he did not know how activities begun in his time played out over the next century: the successful centralization of an English monarchy, a sweeping monastic reform of the church, and the incorporation of Viking communities into the realm.

Thus Aldred’s uniqueness gives us a perspective on tenth-century England from a different temporal and geographic angle. For Aldred, the Northumbrian past was a living and present thing, vital to the English future. He, with the community of St. Cuthbert at Chester-le-Street, saw himself as a link in this temporal chain. Northumbria still had resources of value to all of the English: for the rise of Wessex, they had the body and spirit of Cuthbert as patron saint; for church reform, they offered liturgical experimentation, albeit their efforts went virtually unrecognized; and for the Viking presence, they offered a pattern of integration into the Christian community. But perhaps the best historiographical insight comes from what Aldred did in the manuscript now housed as a national treasure in London, his Old English gloss and bilingual colophon in the Lindisfarne Gospels.

To most eyes, Aldred’s contribution to the Lindisfarne Gospels appears static and backward looking, something that modernity undervalues in favor of forward-looking change to the new. His script is old-fashioned, his dialect local, and his Latinity questionable, all evidence used to demonstrate the low point reached by the Lindisfarne survivors at Chester-le-Street in the late tenth century. Nonetheless, his colophon at the end of the manuscript reveals that his local and old-fashioned preferences may have been deliberate archaizing. He places himself, rather cleverly, in direct connection to the eighth-century golden age preserved in the Lindisfarne Gospels, and values his own contribution as equal to theirs. The colophon is actually quite complex, code-switching between Latin, the universal language of Christianity, and the local vernacular Old English.[xviii]

The brief poem cited at the outset Aldred wrote into the right margin of the last section of the gospel of John he had recently finished glossing:

+May the letter, faithful servant of speech, reveal me; greet, O kind one, all my brothers with [your] voice.[xix]

These Latin verses address the present and future members of his religious community in a personal way: he wants to be remembered after his death by the fruits of his labor, as a wordsmith.[xx] Aldred’s fixation with the power of words continues in the main colophon below the end of the Gospel. [….][xxi]

Much more can and has been said about this colophon, usually focused on what it tells us about the original construction of the manuscript in the eighth century, rather than the tenth-century community of St. Cuthbert at Chester-le-Street or Aldred himself.[xxii] But by revealing, however briefly, his identity and motives to his community—past, present, and future—Aldred also reveals himself to us; and in reverse, we see his community through his eyes, a lens with a very different sense of time and place. Aldred acknowledges the golden age production in his hands and its creators, but he does not seem to acknowledge the reduced circumstances of the community at Chester-le-Street, to which he paid admission with both money and this skillful work. Moreover, the glossing in Old English is seen as an enhancement to the manuscript, not as a concession to weak Latinity. He was probably commissioned to do the task based on his expertise: able to translate Latin into Northumbrian Old English, able to write in an older script appropriate to this legacy manuscript.

In short, this is not a moribund community barely hanging on in a time of turmoil but one full of pride in its heritage. Why, given the material poverty so obvious to us? Because of the spiritual, atemporal riches they possessed, which we are less able or willing to measure. Aldred is quite clear on the powers that sustain his community in his dedication to God and St. Cuthbert. To Aldred and his community, the spiritual presence of a “dead” saint is worth more than gold and silver. Arguably Wessex kings thought so also, in bringing their gifts of books and gilt liturgical furnishings to honor the saint and win his favor. To understand how powerful the living presence of the past can be to a medieval community long dead to us moderns, I turn to the contemporary Pacific, where resurrecting the pre-contact past in the post-colonial present is a matter of vital importance to the future.[xxiii]

The View from the Pacific

The Pacific as a geographic and cultural zone has a similar, though not identical, temporal divide to medieval and modern running through it: pre- and post-contact. This Euro-American colonial marker has generated a second divide into the post-colonial present. In turn, postcolonial historiography, with postmodernism, addresses the question of “what now?” as voices from former colonies around the globe struggle to reclaim their own sense of history while wrestling with the hegemony of a western narrative of progress. Contemporary scholars of the Pacific, speaking as mediators from within their respective cultures and from within the academy, highlight colonialist destruction and desecration of their lands and histories. These scholars are exploring a sense of place in the unique histories of distinctive island groups amid a pan-Pacific identity that cuts across time, based on shared stories of origin and migration as well as linguistic and artifactual similarities that speak to the interconnections between zones of settlement (currently divided into Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia).[xxiv] This ongoing process of ethnogenesis—both recovery of almost lost ancient ways of thinking and the creation of new forms of connection to the past—offer perhaps the best in new historiography from which all historians could benefit. In particular, Hawaiian and other Polynesian societies have a rich notion of living and feeling history that stands in stark contrast to the dead, objectifying historical discourse of modernity.

At the heart of history in almost any culture, including “Anglo-Saxon” as well as Pacific societies, is the notion of storytelling linked to genealogy. Ethnogenesis is more than a recent theory, but a very human way of thinking: Who are we and how do we belong to each other and to this place?[xxv] The Hawaiian word mo‘olelo (“story”) in practice conveys a sense of kinship between land and people, the dead and the living. Indeed, ka wā ma mua in the Hawaiian language defines the past not only as the time before but as in front. Similarly, ka wā ma hope is the time after or behind, that is the open and unknowable future.[xxvi] In essence, the past is before us and the future is behind us in a way that Aldred would understand as he looked back in the Lindisfarne Gospels colophon while speaking forward. In this conception of history and memory, one faces the past while moving backward into the future because, unlike the future which we cannot see and which is not fixed, our eyes can survey and interpret what came before as a guide to the future we are backing into. In some ways, this view mirrors Kierkegaard’s assertion that “life can only be understood backwards,” but the philosopher’s actual emphasis was on the limitations of that truism because life must also be “lived forwards;” it is impossible to “rest” in the backward-looking position except perhaps through the illumination of a life-view, so that “life is lived backwards through the idea.”[xxvii] This resonance between a western philosopher and Hawaiian historiography may be because Kierkegaard’s views are more medieval Christian than modern and secular: his view of time is similar to Bede’s Incarnational history.[xxviii] Kathleen Davis points to Bede’s open and unfixed view of future time, in contrast not only to some of his contemporary Christians but also in contradistinction to the modern progress view of history resolutely facing toward a foretold future that medievalizes a dead past.[xxix] While Davis compares Bede’s historiography to Amitav Ghosh’s In An Antique Land, this essay draws a different parallel with Pacific historiographies as a way out of the modern/medieval conundrum Davis exposes but does not resolve.[xxx] To do so, I turn to an early twentieth-century bicultural historian of the Pacific who offers some other ways of reading tenth-century Northumbria.

Te Rangi Hiroa or Sir Peter Buck (1877-1951) was a Maori-Irish medical doctor, anthropologist, author, and director of Honolulu’s Bishop Museum, whose collection of Polynesian artifacts and histories he helped built. Hiroa/Buck—the slash an admittedly awkward way of recalling his hybrid heritages—was an early proponent of a pan-Pacific identity traceable in islander stories of origins and migration, although his views on kinship “blood” are heavily colored by early twentieth-century racial genetics derived from his western academic training. Author of Vikings of the Pacific (1959; originally Vikings of the Sunrise, 1938), the title and introduction of this book invoke a comparison between the maritime history of the Vikings and that of the Polynesians.[xxxi] His overview of world maritime history traces the center of gravity swinging from the Mediterranean, to the North Sea, to the Atlantic, then finally the Pacific to highlight his Polynesian Vikings of the “sunrise,” whom he designates the “supreme navigators of history” in line with a romantic and Victorian conception of the Norsemen as “bold, intrepid mariners,” not marauders.[xxxii]

In terms of methodology, his book combines “more human” oral histories gathered from fellow Polynesians with the western (and arguably less humane) methods of “measurements, measurements, and yet more measurements.”[xxxiii] Ironically, the latter scientific measurements he offers are now completely out of date and even racially offensive, while the former, the primary accounts and personal stories, continue to provide valuable ethnographic information from native informants. In his consideration of cultural diaspora in the Pacific, Buck identifies Polynesian mariners as “Europoid” (i.e., Caucasian) and not “Negroid” or “Mongoloid,” based on stature, head measurement, skin tone, hair type, and nose width (Maoris have “the narrowest noses in Polynesia!”), concluding: “Sufficient for the day is the fact that a tall, athletic people without woolly hair or a Mongoloid eyefold had the ability and courage to penetrate into the hitherto untraversed seaways of the central and eastern Pacific.” [xxxiv] This precocious Polynesian strain, even when mixed with Mongoloids or Negroids, he portrays as superior, particularly to the Melanesians, views contrasting starkly with his sympathetic portrayal of Polynesian islanders with whom he feels kinship through his Maori heritage.

The tensions over identity and ways of thinking that Hiroa/Buck reveals about himself in Vikings of the Pacific challenge our notion of what it means to “belong” to a community and also highlight the instability of the medieval/modern and pre-/post-contact divides. Instead, Hiroa/Buck offers some possibilities for spiritual kinships that cut across human-constructed boundaries of time and geography in a way that may help us understand Aldred’s spiritual community in tenth-century Northumbria. Both situations reveal a complex mediation occurring between a distinctive local identity that ties genealogy to land and a larger atemporal conception of belonging to some global migratory community, whether Christendom or pan-Polynesia. Neither one is accommodated by the modern nation-state construct with its secular materialist underpinnings and ethnic nationalisms.

First of all, linguistic and emotional senses of community are inextricably linked in Vikings of the Pacific. Like many bicultural translators and writers, Hiroa/Buck functions as a “go-between,” a label Kathleen Biddick also applies to Bede in the conversation she imagines he has with a modern Chicana feminist scholar about bilinguality.[xxxv] Hiroa/Buck, “writing in English and thinking in Polynesian” wrestled with his linguistic hybridity. His father from the north of Ireland, his mother Maori, he describes himself as “binomial, bilingual, and inherit[ing] a mixture of two bloods that I would not change for a total of either…. My mother’s blood enables me to appreciate a culture to which I belong, and my father’s speech helps me to interpret it.”[xxxvi] Here language and rationality are linked in opposition to blood and feeling, with the scientific operating as the interpreter of the genetic and emotional. This racialized view of genealogy is not from his Maori side, but a modern construct from his medical education imposed on Polynesian senses of blood and kinship, in a way similar to nineteenth- and twentieth-century efforts to establish ethnic nationalities in Europe based on medieval linguistic constructions of identity.

Nonetheless, despite or because of his scientific training, the incommensurability of language in translation cuts deeply into Hiroa/Buck’s interior dialogue between his two halves. In one instance he retells the voyaging story of Ru in the Cook Islands, a story his hosts offer him because he was “blood of our blood and bone of our bone.”[xxxvii] As recording ethnographer he then wrestles with the translation of Ru’s invocation of the god Tangaroa: “‘Tangaroa i te titi,/ ‘Tangaroa i te tata” he translated in his own bilingual mind as “Tangaroa in the titi, Tangaroa in the tata,” thinking it a “mere” play on sounds. When he asked the meaning of titi and tata, the elderly chief indicated with the sweep of his arm the whole horizon and replied: “Can we find words? Are not titi and tata as good as anything else to represent what we cannot express?” Hiroa/Buck then moves through his two linguistic modes of thinking. First he translates the phrase into English and western conceptual terms, using his father’s speech to render the lines as “the immensity of space.” Then he code switches back and says to the chief: “‘Yes…Tangaroa in the titi, Tangaroa in the tata. It could not be better expressed,’” adding in the book (emphasis mine) “I thought so then, and I feel more so now.”

That sense of incommensurability of thought and feeling lurks also in the bilingual glossing work of Aldred, but in some ways reversed: the Latin language is the measured, formal terms that Aldred seeks to express in his native Northumbrian language, often using calques, alternative words, and in some cases offering literal followed by interpretive glosses reflecting a range of theological meanings available in medieval Biblical exegesis.[xxxviii] Aldred as a “go-between” negotiated the boundary between the universal Latin language of Christendom and the Northumbrian-inflected English of his community. Like Hiroa/Buck it is Aldred’s native language that runs deeper in “feeling,” an aspect historians tend to psychologize rather than see as part of real systems of meaningful connection.

Hiroa/Buck’s emotional commitments to his communal heritages also illustrate a western binary of belief as feeling versus rationality, with a colonial twist on Irishness. Throughout the book, he exhibits considerable ambivalence about his mixed genetics, saying early on “with all my love for my mother’s stock, my father’s unbelieving blood gives me pause,” and yet he credits his historical empathy to both: in discussing a particular chant, he notes that “the words are simple, but perhaps only the Polynesians and the Irish [my emphasis] can feel the depth of poignant grief expressed in simple words.”[xxxix] This comment actually replicates a Victorian, as well as British colonial, notion of the emotional Irish, where loquacious feelings and storytelling displace rationality and underlie the Catholic superstition associated with a lingering medievalness in the Irish. For example, in 1926 Charles Plummer compared the prolific and self-revealing colophons of medieval Irish scribes to encounters modern travelers to Ireland might have with an Irishman who “will discuss his most intimate private affairs with any casual stranger whom he may happen to meet;” while “the relief which the modern Irishman finds in this kind of conversation” is given as an ethnic trait which the presumably stiffer Englishman finds uncomfortable.[xl] Embedded in these remarks are a set of encoded social and scholarly values about Irish difference: that scribes normally should be subservient to the text they copy and not insert their personal lives into the manuscript; that real scholars remain emotionally distant from their subjects to retain a scientific objectivity; and that the Irish, then and now, transgress social as well as scholarly boundaries, at least from the perspective of their cultural superiors as represented by Plummer. The upshot is that the Irish remain medieval and colonized.

Unsurprisingly Aldred’s colophon in the Lindisfarne Gospels fits this Irish mode of intimate and revealing colophon writing Plummer describes so paternalistically. Consequently, Aldred also speaks from a historiographically and socially marginalized position, in the eyes of early modern historians at least, as emotionally “too Irish” and not West Saxon enough, textually “too superstitious” in his Catholic liturgy and not sufficiently proto-Protestant enough, and altogether too medieval for the modern, forward-facing imagination.[xli] Curiously, Hiroa/Buck performs the same action as Plummer on himself, but with different results: the combined Maori and Irish capacity for feeling stands in contrast to the cool (modern, western) scholar with his tools of measurement. That scientific detachment must be, then, only a veneer on his Maori/Irish self, useful measures to deploy at will, but also to discard, as well we might today in reading Vikings of the Pacific with its distasteful racial categories. In many ways, Hiroa/Buck was living in limbo between colonizer and colonized, with the latter doubled, perhaps invisibly to him, since both Irish and Maori were colonial subjects of the dominant British and western academic sciences.

Although Hiroa/Buck imagines himself as bicultural, his hybridity is actually more complex, reflecting layers of historical memories: Maori and New Zealander, Irish, English, and even Viking. The overall tenor of Vikings of the Pacific suggests that Hiroa/Buck’s emotional affinities ran deeper than the scholar-speak he adopts. In one instance, he notes that he could not take skulls as museum artifacts because he says, “I have a feeling—a superstition, if you will—that if I did, I would destroy the sympathetic relationship that exists between their past and me.”[xlii] Insofar as superstition is a belief inconsistent with one’s worldview, Hiroa/Buck has a problem for he has two worldviews operating simultaneously that he tries to meld but which leave him in the dubious position of finding a rational belief in one system appear inconsistent and therefore superstitious in the other: the scientific belief in genetic determinism stands in opposition to the Maori sense of kinship with the dead.[xliii] Thus the cataloging scientific approach threatens to break the bond that allows him to extract vital cultural data from his informants. He chooses the feeling, superstitious as it may appear from the science side of himself, and in so doing, he shows that the imagined community of Polynesianness is stronger than the adopted western heritage of scientific analysis.

In this instance of “skulldudgery,” Hiroa/Buck could just as easily have drawn not only on his Polynesian sense of place but also his Irish roots to access medieval Christian views of the sacred dead in the landscape—except that Hiroa/Buck’s understanding of his Irish heritage is so heavily colored by layers of British, Protestant, and modern rationalism that he was not able to make that connection in the way he did with the Polynesians and the Vikings as master navigators.[xliv] In fact, his father’s family was Anglo-Irish Protestant with clerical ancestors at Trinity College, Dublin; he had little contact with the Irish side of the family and never visited Ireland, although he married a “fiery” Belfast born Irishwoman.[xlv] Given the very Anglican name of Peter Buck at birth, Maori tribal elders granted him in his teens the ancestral name Te Rangi Hiroa.[xlvi] This genealogically based naming and renaming illustrates a sense of continuity: the presence of the dead in the living demonstrates how the past confers meaning on the present.[xlvii] Western honorifics occurred later in life. New Zealand belatedly conferred knighthood in recognition of his achievements for his homeland, at a time when he was living and working in Hawai‘i as director of Bishop Museum (from 1936 until his death in 1951). When the King of Sweden awarded him the Order of the North Star in 1946, a physician friend, Dr. Nils Larsen, at the ceremony in Honolulu engaged in a fake Viking blood brother ritual with him, a joke probably only apparent to the two men.[xlviii] The Irish blood Hiroa/Buck claimed to be a part of his emotional makeup may be as fictive a kinship as the Viking blood he exchanges: it is notional more than actual, relying on a trope of Irish character as represented through the lens of British colonialism.

If he had been able to tap the medieval Irish roots obscured by his British Protestant birthright, he might have noted not only the Viking-Irish foundation of Dublin but also the spiritual sensibilities that echoed faintly in his sense of common feeling between his Irish and Polynesian blood and that prevented him from removing the skulls to a museum. The repatriation of bones today, like the medieval translation of a saint, is a serious political act, often as not intending to redress or undo colonial damage. But in emphasizing the political as secular in our modern way of seeing things, we often overlook the spiritual power and emotional bonds connected to the dead as these subject cultures resist not only the colonizer’s political agency but also modernity as a historical colonizer of their past.[xlix]

Similarly for our understanding of tenth-century Northumbria, Cuthbert’s bones are a vital clue to cultural relations with Ireland and Wessex. At one point as the community of St. Cuthbert moved away from the Viking-induced political turmoil around Lindisfarne, they attempted to take the saint’s body to Ireland for safety. However, the saint at the pleas of his people turned them back so that Cuthbert stayed on Northumbrian land.[l] Moreover, over the next century with the assertion of Wessex control of Northumbria, no records suggest that any Wessex king attempted to move the body of Cuthbert away from Northumbria into Wessex. The saint was, and is, immovable, his permanence in the landscape based on a spiritual potential. Thus it is that Northumbria in the person of St. Cuthbert was not to be colonized by anyone and maintains a distinctive identity tied to the lands north of the Humber to this day. I daresay if someone from outside Britain tried to move Cuthbert’s bones from his Durham Cathedral tomb today, there would be a political uproar, and perhaps even invocations of the curse of Saint Cuthbert, a superstition excused by feelings of local or national pride.[li] Yet, the casual manner in which EuroAmerican researchers acquired and displayed Pacific islanders’ bones ostensibly justifies itself based on a modern secular and materialist view of death as inconsequential and therefore of the past as dead; but this view apparently only applied to other people’s histories, not one’s own. Caught on the fence between these views, Hiroa/Buck’s Maori sense of kinship to the past won out. Indeed, Hiroa/Buck’s imagined Polynesian community stretching across the Pacific was solid enough to undercut the western scientific rationalism impinging on islanders’ historical memory, although he was unable to do so with his Irish heritage medievalized by modern secularism.

Hiroa/Buck’s cultural conflict between his Irish and Maori affections and his western intellectualism also correlates with the historiographic temporal divide Davis exposes, where thought is modern and feeling is pre-modern or not modern, a dream of the past that is unreal.[lii] While musing on the “virile branches” of Polynesians in the Marquesas, he asked “Can we ever see the throbbing past except in dreams? I do not wish to awake, for when I do, I will see but a line drawing in a book that conjures up a lone terrace overgrown with exotic weeds, and sad stone walls crumbling to decay.”[liii] His Maori sense of history, similar to the Hawaiian mo‘olelo, is rooted in the oral transmission of stories: what links him to other Polynesians he visits are the ritual exchange of genealogies and “ancient traditions,” which he first had to master in his Maori homeland from his grandmother and other elders.[liv] In another revealing passage on Maori history and identity from his twin perspectives, he concludes by leaving them “to work out their own salvation in the firm conviction that the stamina and mentality inherited from their stone-age ancestors will enable them to make good in a changing world.”[lv] After these allusions to a Christian and then a scientific view of historical progress, he then ends the chapter by bidding farewell to the land of his birth with a translation of a dirge for a chief that has a distinctly ubi sunt feel to it.

Such hybrid passages point to an interesting feature of Hiroa/Buck’s historiography: when he speaks from within his Polynesian sense of history, his views are firm and real; when he is caught in the modern/scientific progress view facing the future, his uncertainty and dislocation toward the past is palpable. From this conflicted position, what Hiroa/Buck offers us is a way to tap a more vital, living sense of history in contrast to the deadening and objectifying of modern, secular historiography, one that connects the living and the dead and is tempered with a dose of humility. In some ways, the stories Hiroa/Buck recounts capture the same communal sense of identity and deference to ancestors found in early English historical narratives like Bede’s ecclesiastical history.

This “feeling” is precisely what is lacking in many ethnographies and histories of migration: the way that a communal sense of place has a spiritual dimension in the formation of cultural identities in “non-modern” societies. A sense of connectedness is most evident in the evocative style of first person narrative Hiroa/Buck uses in Vikings of the Pacific. When he is telling Polynesian stories he understands from within his Maori upbringing, his voice is rich with a sense of intimacy, the color of his language deep hued compared to the black and white of dialectical scientific analysis. Similarly, Aldred played across the linguistic boundary between impersonal, universal and timeless Latin and the intimacy of the local vernacular of his contemporary community, done as part of a spiritual act of worship. Go-betweens like Hiroa/Buck and contemporary Pacific historians can teach us how to break out of the objectifying mold of academic language (even, and maybe especially, the trap of postmodern theory speak) by drawing on a personal sense of connection to people of the past through narratives of encounters and continuities, not just analyses of spatial and temporal dislocations found in medieval/modern or pre-/post-contact.

Thus despite or because of his mixed legacy of western colonial racism and islander perspectives, Hiroa/Buck offers some lessons for decolonizing the Middle Ages. For example, his Viking and Polynesian comparative historiography is instructive, inviting us to rethink the maritime zones of the Atlantic and North Sea. On a larger, world historical scale, he describes an oceanic sense of place at odds with the western nation-state with its terrestrially bounded seas. Next generation Pacific historian Epeli Hau‘ofa has articulated how, for Polynesian societies and their mariners, the ocean is their home and the islands simply locations within that landscape, in contrast to the western explorers’ sense of the ocean as a vast, empty space through which one must traverse to get “to” someplace.[lvi] Similarly, the British Isles can be seen through the lens of waves of migration inhabiting coastal zones that faced water. Archaeological and anthropological evidence suggests that over the longue durée of this Atlantic and North Sea zone, various people groups came to its shores, often as not facing outward, not inward toward unifying the landmass.[lvii] When the Vikings roamed this same zone and beyond, they saw the world as shores connected by water: with globe rotated to place the North Atlantic at the center, the seaways connecting Scandinavia westward to Scotland and Northumbria, Ireland, Iceland, and Greenland, on to North America are obvious.[lviii] That was, in effect, Aldred’s world, defined by overlapping zones of contact and interacting people groups more so than the rise of a central monarchy that he, unlike us, would have seen as a temporary phase in a longer spiritual history of his community.

Later, Captain Cook mapped the same terrain as the Vikings in Newfoundland and Labrador, not to mention archipelagos in the Pacific. Today, Cook is memorialized with statues and museums at his home port of Whitby, in Newfoundland, and on the Big Island of Hawai‘i where his death is the subject of competing historiographical narratives.[lix] Hiroa/Buck mentions Cook as a “rediscoverer” of islands and the source of contemporary names assigned them, siding for example with the “peaceable and industrious people” of Niue objecting to Cook’s renaming of their home as Savage Island because someone threw a spear at him—and missed: “Why should an individual failure be perpetuated on the descendants of a bad marksman?”[lx] Because names tell a story, renaming, like the removal and restoration of bones and artifacts, is a political act of disempowerment or re-empowerment. Hiroa/Buck’s ironic query puts Cook in his place within a larger and longer history of Polynesian peoples.

Because Hiroa/Buck stands at a geographic and temporal nexus, he can speak from within multiple stories, albeit not always harmoniously. Yet Vikings of the Pacific contains alternative models more inclusive of the spiritual dimension so absent from modern and even postmodern discourse about identities and communities. Hiroa/Buck traces different versions of Polynesian origins for the islands and its people groups. Some, like the Sāmoans, focus on a sense of their island as a sacred center from which they emerged, seemingly in denial of the western constructions of their migration history from elsewhere. This leaves the outsider historian pitting a “religious” legend against an evidence based and seemingly objective account that therefore must be “really true,” at least from a western scientific view. The same might be said of trying to reconcile Bede’s account of English history with the archaeological record: which is more truth-telling depends on your view of what is essential.

Similar to these contrasting accounts of human migration and origins, stories of the formation of Pacific island chains vary.[lxi] The more widespread Polynesian account of the emergence of island chains is the story of Maui fishing up the islands. But as in many cultures, including the accounts of creation in Genesis or the origins of the Anglo-Saxons, several alternative storylines are available. In Hawai‘i, one account has Papa-hanau-moku giving birth to the islands fathered by Wakea or made directly by his hands.[lxii] But the nineteenth-century Hawaiian historian David Malo (1795-1853) found the competing oral accounts from the ancients contradictory, preferring the genealogical Kumulipo creation account of the islands emerging on their own, without the birth narrative, as easier to synchronize with the “speculative” geologic theories of volcanic origins.[lxiii] Interestingly, Hiroa/Buck questions Malo’s westernizing syncretism: “Yes, who knows? Probably the geologists will support David Malo and the Kumulipo, for the like of Wakea and Papa are not to be seen today.”[lxiv] Hiroa/Buck’s doubt, and sense of loss, opens the way for a different epistemology that can accommodate seemingly incommensurable “truth-telling” narratives. We can choose, then, to put these accounts on a level playing field without marking them on a temporizing scale of less to more truth, from primitive oral myth through medieval superstition to the modern rational.[lxv] Instead, we might consider the spiritual connections Aldred and his community felt as more than imaginary.

We return then to Hiroa/Buck’s epilogue to Vikings of the Pacific quoting the Maori proverb “the old net is laid aside; a new net goes afishing” and ending with the poignant query “What new net goes afishing?” Although he laid the foundation collecting and storing oral histories during his time as Director of the Bishop Museum in Honolulu, Hiroa/Buck did not live to see the Hawaiian renaissance of the 1970s and the recreation of Pacific navigation by the Polynesian Voyaging Society that saw the old nets repaired.[lxvi] The double-hulled sailing canoe Hōkūle‘a made the roundtrip from Hawai‘i to Tahiti with startling “scientific” accuracy (in terms of modern instrumentation) using “traditional” wayfinding methods derived from chants, oral histories, and most crucially, from the memories and experiences of one living Micronesian navigator, Pius “Mau” Piailug (1932-2010).[lxvii]

Hiroa/Buck would undoubtedly find in this and subsequent recreated voyages validation for his Vikings of the Pacific narrative of Polynesian migration, perhaps even happy to see the “scientific” racial theories within which he operated discarded, overturned by the accuracy of cultural information contained in oral histories that he had a hand in preserving. But he might also be stymied, as many contemporary Pacific writers are, by the continuing devaluation in secular academic discourse of the power of spiritual communities across time and place. Similarly, hybridized Northumbrians like Bede and Aldred might be both gratified at what survives from their era of the Irish, English, and Viking heritages and chagrined at the loss of spiritual community between the living and the dead they valued so highly.

These spiritual communities in Hiroa/Buck’s Polynesian ethnography and Bede’s Anglo-Saxon history are more than emotional communities; they are not imagined or theorized, but narratives breaking out of the dialectic of colonizer and colonized, medieval and modern, religious and secular. Imbedded in that dialectic are more subtle but pervasive values drawn from modernity and still infecting the academy, where the subjectivity of lived experience, beliefs, and personal connection to the past belong to literary studies of fiction and autobiography, while scholarly historical writing retains a preference for scientific observation that is “objectively more true,” at least based on a materialist worldview.[lxviii] Hybrid voices from the twentieth-century Pacific, like Hiroa/Buck, offer us a way out of this dualism and entry into the medieval past and its “pre-modern” worldviews. When marginal figures like Aldred are moved from the periphery into the center, at the point of contact between times and places, they allow us to hear the polyphony in what often becomes a monophonic historical narrative. The Hawaiian word kaona conveys this sense of unwrapping layers of meanings through dialogue, both transmitted orally and in cross-cultural translation efforts.[lxix] This essay similarly has been structured around unwrapping layers of meaning in the way we relate to the past and therefore concludes with an examination of those wrappings.

Conclusion and Colophon

The Pacific view of Northumbria sketched in this essay has at least three implications. First, echoing Davis’ work, all historians need to be wary of the lurking medieval/modern divide in western colonial discourse that affects our understanding of both the European past and the global present. Second, we need to query the secularization theory of modernity while paying more attention to the spiritual powers at work in historical memory, by evoking feelings of connection as well as valuing thoughtful objectivity. And third, in order to do both of these, we should consider the world/comparative possibilities for developing a Pacific historiography that can help rewrite European history out of its periodization mire.

The previous paragraph does the expected work of a conclusion in academic discourse: it makes generalized recommendations in the invisible third person, in which the author remains an omniscient narrator. But in so doing, the conclusion fails to take its own advice and apply the lessons gleaned from Pacific historians. At the outset, this essay proposed an authoethnographic mode to escape the colonizing and secularizing influence of the modernist project. The author-historian who brought Aldred and Hiroa/Buck together needs to acknowledge her own position in relation to the two subjects in order to generalize to other historians the lessons she derived from serving as a go-between bridging tenth-century Northumbria and the twentieth-century Pacific. Like Aldred, I have erased the “I” from the main narrative history but am prepared to add some personal genealogy into the margin.

In terms of heritage and identity, I cannot claim to be either Northumbrian or Hawaiian. While some of my ancestors came to the Americas from the British Isles and perhaps even Northumbria, my Englishness is indirect and distant, derived from Anglo-American Protestant culture. As a consequence, my relation to Northumbria is studied more than lived, although the boundary between the personal and scholarly experience is more blurred than most historians will admit: I have come to know Aldred and his tenth-century community through time consuming, arguably obsessive, scrutiny of manuscript artifacts; and while conducting research on site, I have interacted with and received support from contemporary scholars who are also Northumbrians.[lxx] Meanwhile, I have lived in Hawai‘i for over thirty years where I remain a haole (foreigner) in relation to the Kānaka Maoli (indigenous Hawaiians), but also a kama‘āina (child of the land) in the inclusive understanding of residency fostered by the Hawaiian kingdom.[lxxi]

Thus despite my outsider status in relation to both geographic zones, I experience a “sense of place” in both the contemporary Pacific with its ways of looking toward the past and tenth-century Northumbria as it manifests itself today in the surviving artifacts and landscape north of the Humber river. As a consequence, I feel some kinship with Aldred analogous to Hiroa/Buck’s connection to his Polynesian informants. Living as a kama‘āina and observing Kānaka Maoli both recovering and establishing their historical voices has enriched my own understanding of culture and identity, while raising serious questions about the methods of history. From this position in a triangular relationship with cultural translators Aldred and Hiroa/Buck, I become like them, a go-between writing a colophon addressed to fellow historians about our scholarly pursuit—our calling, if you will.

If we as historians stand outside of any time and place, we are also simultaneously seeking to be within a particular time and place. Pacific historiographies offer us a way of negotiating that dual role. In a sense, they suggest discarding the newer net of modern, objectifying dialectic for an old net, repaired and made whole and usable for understanding the past as something intimate and alive. Two sets of challenging questions emerge:

Can we evacuate the dialectic historiography of modernity that presently takes up so much space that we have no room to tell a story with feeling? Can we get beyond the nation-state frame of reference and colonialist periodization? To undo the medieval/modern divide, we need to reach back further, learn to narrate history over again, to tell a story as Bede or Hiroa/Buck did, finding a voice from within our hybridity while revealing, like Aldred in his colophon, our go-between status as cultural translators.

Are we willing to allow the dead to be a part of us, include them in our story, and allow them to speak to our present, postmodern condition? Are we willing to stop taking the past apart and begin constructing whole narratives? Our ancestor historians from across time and place call us to feel as well as analyze who we are as we turn our face toward the past and listen to them a bit more intently.

This essay’s title, “Vikings of the Pacific: An Oceanic View of the Early Medieval British Isles,” may merely serve to expose a particular historian’s perspective, looking back at a community almost half way around the globe over a millennium ago, but it also asks all historians whether that temporal and geographic distance adds to or subtracts meaning from the past.

[i] A free translation of Littera me pandat sermonis fida ministra./ Omnes alme meos fratres voce salvta. London, British Library, Cotton Nero D.iv (Lindisfarne Gospels), fol. 259r. For a facsimile, see the British Library website Turning the Pages: Pinnacle of Anglo-Saxon Art (http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/ttp/ttpbooks.html).

[ii] Peter Buck, Vikings of the Pacific (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1959), p. 325.

[iii] Carolyn Ellis, Tony E. Adams, Arthur P. Bochner, “Autoethnography: An Overview,” Forum: Qualitative Social Research 12.1 (January, 2011), Art. 10 (http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1589). Jeremy D. Popkin, History, Historians, & Autobiography (Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 2005), pp. 15, 285, on the sublimation of historians’ selves in relation to their subject.

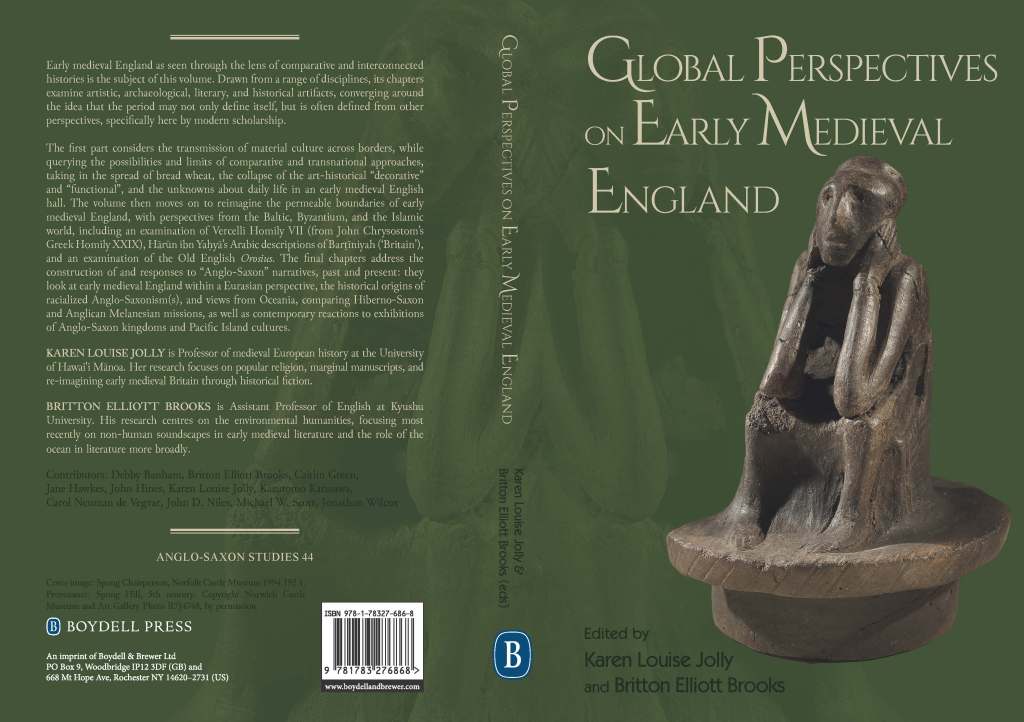

[iv] See now Neil Price and John Ljungkvist, “Polynesians of the Atlantic? Precedents, potentials, and pitfalls in Oceanic analogies of the Vikings,” Danish Journal of Archaeology (2018) DOI: 10.1080/21662282.2018.1498567; Michael W. Scott, “Boniface and Bede in the Pacific: Exploring Anamorphic Comparisons between the Hiberno-Saxon Missions and the Anglican Melanesian Mission” in Global Perspectives on Early Medieval England, ed. Karen Louise Jolly and Britton Elliott Brooks (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer), 2022, pp. 190-216; Madi Williams, Polynesia, 900-1600 (Leeds: Arc Humanities Press, 2021); and James L. Flexner, Oceania, 800-1800CE : a Millennium of Interactions in a Sea of Islands Cambridge: (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

[v] For perspectives on Hawaiian history, see Lilikalā Kame‘eleihiwa, Native Land and Foreign Desires: Pehea Lā E Pono Ai? (Honolulu: Bishop Museum, 1992); Haunani-Kay Trask, From a Native Daughter: Colonialism and Sovereignty in Hawai‘i (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1993, rev. ed. 1999); Jonathan Kay Kamakawiwo`ole Osorio, Dismemebering Lāhui: A History of the Hawaiian Nation to 1877 (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2002); and Noenoe K. Silva, Aloha Betrayed: Native Hawaiian Resistance to American Colonialism (Durham : Duke University Press, 2004); and now Noelani Arista, The Kingdom and the Republic: Sovereign Hawai‘i and the Early United States (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2019); and a more recent overview in Karen Louise Jolly,“Anglo-Saxons On Exhibit: Displaying the Sacred” in Global Perspectives on Early Medieval England, ed. Jolly and Brooks, pp. 217-44.

[vi] M. Puakea Nogelmeier, Mai Pa‘a I Ka Leo: Historical Voice in Hawaiian Primary Materials, Looking Forward and Listening Back (Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 2010), points to the large body of nineteenth-century Hawaiian language newspaper sources, the product of one of the most highly literate populations in the world.

[vii] Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999), pp. 31, 34. See also Paul Lyons, American Pacificism: Oceania in the American Imagination (New York : Routledge, 2006) on the distorted perceptions of the Pacific in American literature and culture.

[viii] Carol Symes, “When We Talk about Modernity,” AHR 116 (2011): 715-26, at p. 725.

[ix] Still detected in textbook master narratives, while historians of “Anglo-Saxon England” increasingly emphasize the diverse and problematic nature of English identity and its political formation; most recently Robin Fleming, Britain After Rome: The Fall and Rise, 400-1070 (London: Penguin, 2010) has eschewed narrative sources in favor of material evidence. But see now the vast literature, some cited in Jolly and Brooks, eds. Global Perspectives on Early Medieval England, Introduction.

[x] Take a look at the 1867 Alapaki Ka Nui biography right after Kamehameha I. See also L.No‘eau Peralto, ‘Portrait. Mauna a Wākea: Hānau Ka Mauna, The Piko of our Ea’, in A Nation Rising: Hawaiian Movements for Life, Land, and Sovereignty, ed. N. Goodyear-Ka‘ōpua, I. Hussey, and E. Kahunawaika‘ala Wright (Durham, 2014), pp. 233–43; and essays in Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawai‘i, ed. H. K. Aikau and V. V. Gonzalez (Durham, 2019),

[xi] See for example, David Hanlon, “Sorcery, ‘Savage Memories,’ and the Edge of Commensurability for History in the Pacific,” in Pacific Islands History: Journeys and Transformations, ed. Brij V. Lal (Canberra: The Journal of Pacific History, 1993), pp. 107–128. See now also Hanlon, “Losing Oceania to the Pacific and the World,” The Contemporary Pacific 29.2 (2017): 285-318.

[xii] For an overview of Northumbrian history, see David Rollason, Northumbria, 500-1100: Creation and Destruction of a Kingdom (Cambridge, 2003); for the eighth century, see Jane Hawkes and Susan Mills, ed., Northumbria’s Golden Age (Phoenix Mill, UK: Sutton Publishing Limited, 1999); and for the Lindisfarne legacy, St. Cuthbert, His Cult and Community to AD 1200, ed. Gerald Bonner, David Rollason, and Clare Stancliffe (Woodbridge, 1989). Bede’s Ecclesiastical History is available in Latin (Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, ed. Bertram Colgrave and R. A. B. Mynors [Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969]), Old English (The Old English Version of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, ed. and trans. Thomas Miller, EETS 95 [London: Trubner, 1890-91]), and in modern English editions (Bede, The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, ed. Judith McClure and Roger Collins [New York: Oxford University Press, 1994]).

[xiii] Lindisfarne Gospels (London, British Library Cotton Nero D.iv, c. 710-25); see Michelle P. Brown, The Lindisfarne Gospels: Society, Spirituality and the Scribe (London: British Library, 2003).

[xiv] For this era, the main primary sources are the Historia de Sancto Cuthberto, A History of Saint Cuthbert and a Record of his Patrimony, ed. and trans. Ted Johnson South (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2002) and Symeon of Durham, Libellus de exordio atque procursu istius, hoc est Dunhelmensis, ecclesie (Tract on the origins and progress of this the Church of Durham), ed. and trans. David Rollason (Oxford: Clarendon, 2000).

[xv] On King Alfred’s era see David Pratt, The Political Thought of King Alfred the Great (Cambridge, 2007) and on the Old English Bede, see Sharon M. Rowley, The Old English Version of Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2011).

[xvi] On King Athelstan’s donations to the community, see Simon Keynes, “King Athelstan’s Books” in Learning and Literature in Anglo-Saxon England, ed. Michael Lapidge and Helmut Gneuss (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), pp. 143-201; on his donation portrait portrait, see Catherine E. Karkov, The Ruler Portraits of Anglo-Saxon England (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2004), pp. 53-83; on the liturgy, see Christopher Hohler, “The Durham Services in Honour of St. Cuthbert,” in The Relics of Saint Cuthbert, ed. C. F. Battiscombe (Oxford, 1956), pp. 155-91; Gerald Bonner, “St Cuthbert at Chester-le-Street” in St Cuthbert, ed. Bonner, et al., pp. 393-94 and David Rollason, “St Cuthbert and Wessex: The Evidence of Cambridge, Corpus Christi college MS 183” in St Cuthbert, ed. Bonner, et al., pp. 413-24.

[xvii] The wooden church of Aldred’s day has not survived, while stone monuments of local carvers influenced by Viking styles are deemed a cruder type than that produced at Lindisfarne. Meager manuscript production seems not to have included illuminations. See Rollason, Northumbria, pp. 13-19 and Rosemary Cramp, “The Artistic Influence of Lindisfarne within Northumbria,” in St. Cuthbert, ed. Bonner, et. al., pp. 213-28.

[xviii] For detailed analysis of the colophon, see The Community of St. Cuthbert in the Tenth Century, forthcoming.

[xix] + Littera me pandat/ sermonis fida/ ministra ./ Omnes alme/ meos fratres/ voce salvta:,

[xx] Normally the religious community recorded its members in a Liber vitae, although in this case the surviving Durham Liber vitae does not have records for this period, a curious lacuna in a genealogically based historiography that Aldred’s colophon only tangentially remedies.

[xxi] See now Karen Louise Jolly, The Community of St. Cuthbert in the Late Tenth Century: The Chester-le-Street Additions to Durham Cathedral Library A.IV.19 (The Ohio State University Press, 2012).

[xxii] See Richard Gameson, The Scribe Speaks? Colophons in Early English Manuscripts (Cambridge, 2001), items 14 and 15, discussed pp. 10-11, 14-21, 29-32; Lawrence Nees, “Reading Aldred’s Colophon for the Lindisfarne Gospels,” Speculum 78 (2003): 333-77; Brown, The Lindisfarne Gospels, p. 95; and Jane Roberts, “Aldred Signs Off from Glossing the Lindisfarne Gospels” in Scribes and Texts in Anglo-Saxon England, ed. Alexander Rumble (Cambridge: Boydell, 2006), pp. 28-43.

[xxiii] See now Tarren Andrews and Tiffany Beechy, eds, Indigenous Futures and Medieval Pasts, English Language Notes 58.2 (2020), Introduction (pp. 1-17).

[xxiv] See Epeli Hau‘ofa, We Are the Ocean: Selected Works (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2008). See now Karin Amimoto Ingersoll, Waves of Knowing: A Seascape Epistemology (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

[xxv] On ethnogenesis theory, see the summary article by Andrew Gillett, “Ethnogenesis: A Contested Model of Early Medieval Europe,” in History Compass 4/2 (2006): 241-60. For 25 indigenous modes of research, from claiming and storytelling to negotiating and sharing, see Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies, pp. 142-62.

[xxvi] Kame‘eleihiwa, Native Land and Foreign Desires, p. 22; Osorio, Dismemembering Lāhui, p. 7. See now: Baker, C. M. Kaliko., Tammy Hailiʻōpua. Baker, Jonathan Kay Kamakawiwo’ole. Osorio, Kaipulaumakaniolono. Baker, Kahikina de. Silva, ku`ualoha. ho`omanawanui, Kamalani. Johnson, Kekuhi Kanae Kanahele. KealiʻikanakaʻoleoHaililani, Larry. Kimura, and Kalehua. Krug, Moʻolelo : The Foundation of Hawaiian Knowledge (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2023).

[xxvii] Kierkegaard, quoting Daub: Søren Kierkegaard’s Journals and Papers: A Selection, ed. and trans. Alastair Hannay (London: Penguin, 1996), pp. 161 and 63. The imagery is also reminiscent of Walter Benjamin’s mystical reflections in his ninth thesis on “the angel of history” in Paul Klee’s painting Angelus Novus, as well as his sense of a theological base lurking behind the puppet of historical materialism in his first thesis: “On the Concept of History/Theses on the Philosophy of History” (1940) in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York : Schocken Books, 1968), pp. 255, 259-60.

[xxviii] Other medieval moderns, like G. K. Chesterton and J. R. R. Tolkien (notably both Catholic), provide a fascinating bridge across the periodization gap; see Tolkien’s Modern Middle Ages, ed. Jane Chance and Alfred K. Siewers (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2005), pp. 1-13.

[xxix] Davis, Periodization and Sovereignty, pp. 106-114, 123-31.

[xxx] See now Amitav Ghosh, The Nutmeg’s Curse : Parables for a Planet in Crisis (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2021).

[xxxi] The new title is reminiscent of Bronislaw Malinowski’s Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922), although it is unclear what influence his work may have had on Hiroa/Buck. Curiously, there is an earlier, 1905 book called Vikings of the Pacific describing western explorers traveling east into the Pacific: Agnes Christina Laut, Vikings of the Pacific: The Adventures of the Explorers Who Came from the West, Eastward (New York: Macmillan, 1905; reprint 1914). See now also Price and Ljungkvist, “Polynesians of the Atlantic,”p. 3.

[xxxii] Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, pp. 5-6, 13, x.

[xxxiii] Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, pp. ix, 14.

[xxxiv]Vikings in the Pacific, pp. 17-19 See also Patrick Vinton Kirch, On the Road of the Winds: An Archaeological History of the Pacific Islands before European Contact (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), pp. 24-27. See now Moira White, “Dixon, Skinner and Te Rangi Hiroa: Scholarly Discussion of Polynesian Racial History, 1920-49,” The Journal of Pacific History 47, no. 3 (2012): 369–387.

[xxxv] Kathleen Biddick, “Bede’s Blush: Postcards from Bali, Bombay, Palo Alto,” in The Shock of Medievalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 1998), pp. 83-101 at 96-99. See also Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies, pp. 196-99, on her own position as a Maori and a researcher studying Maori.

[xxxvi] Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, pp. x, 268. Hiroa/Buck’s biological mother was Rina, who birthed him for her childless cousin, Ngarongo, wife of William Buck and the mother who raised Hiroa/Buck (Rina died shortly after his birth, but this Hagar-like arrangement was not uncommon).

[xxxvii] Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, pp. 101-02.

[xxxviii] See Community of St. Cuthbert, chapter 5, forthcoming.

[xxxix] Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, pp. 26, 212. In another instance (p. 269), he notes the similarity between Maori mourning the dead by weeping (tangi) and an Irish wake, and comments “on such occasions my two halves could unite as one.”

[xl] Charles Plummer, “On the Colophons and Marginalia of Irish Scribes,” Proceedings of the British Academy 12 (1926): 11-44, at 11. The Irish gift for storytelling appeared in remarks by President Barack Obama on a recent trip to Ireland where he received a copy of Irish author Padraig Colum’s children’s book Legends of Hawaii (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1937), commissioned as part of a series by the Hawaii legislature in 1922: “It just confirms if you need someone to do good writing, you hire an Irishman ” (probably in reference to his two Irish American speech writers); “The Gifts: Hawaiian Children’s Stories,” Irish Times, May 24, 2011 (http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/ireland/2011/0524/1224297638360.html); see also “`Ireland carries a blood link with us,’ says Obama,” Irish Times, May 24, 2011 (http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/ireland/2011/0524/1224297638367.html). Colum overtly compares the Hawaiian stories to medieval European, as well as ancient near eastern stories (Legends of Hawaii, pp. xii-xiii, 215).

[xli] liturgy: Durham A.IV.19.

[xlii] Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, p. 215. On the history of skull collecting and measuring, see David Hurst Thomas, Skull Wars: Kennewick Man, Archaeology, and the Battle for Native American Identity (New York: Basic Books, 2000).

[xliii] On the European intellectual history debating the concept superstition, see Euan Cameron, Enchanted Europe: Superstition, Reason, and Religion, 1250-1750 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

[xliv] Although in one aside, he compares resistance to conversion: “Thus in the Pacific, as well as in the Atlantic, religious intolerance played its part in causing the settlement of new lands” (Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, p. 90).

[xlv] J. B. Condliffe, Te Rangi Hiroa: the life of Sir Peter Buck (Christchurch, N.Z.: Whitcombe & Tombs, 1971), pp. 23, 183. Often characterized as either hot-tempered or warm-blooded, his wife Margaret is accounted a force behind Buck’s ambitions, despite her illness, perhaps alcoholism, toward the end of her life.

[xlvi] His mother initially named him Te Mate-rori (Death-on-the-road) after his maternal uncle, Te Rangi Hiroa, died.

[xlvii] Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, p. 267.

[xlviii] Condliffe, Te Rangi Hiroa, pp. 198-99.

[xlix] Every time new building construction in the islands disturbs the bones of the dead, it is an affront to a local sense of history that faces the past with respect for the presence of the ancestors among us, rather than facing forward toward some mythical or hypothetical future. The clash of beliefs over the place of the dead has recently come to a head at Kawaiaha‘o Church, the early mission site on Oahu (http://www.kawaiahao.org/). While digging the foundation for a new building they discovered graves of Hawaiians, ostensibly Christian burials in the churchyard, but other voices claiming a living connection to these dead believe they should remain undisturbed according to Hawaiian traditions. What were the intentions of the dead and their families at their burial? Similar questions arise about the meaning of changing burial practices in Anglo-Saxon England as explored, for example, by Robin Fleming, Britain After Rome.

[l] HSC 20; Johnson South, Historia, p. 59.

[li] Cuthbert defended his community’s lands from theft, once transfixing a Viking doubter of his spiritual prowess with an iron bar on the threshold of a church (HSC 22-24; Johnson South, Historia, pp. 60-63). For a general history of the cult of St. Cuthbert and its promotion, see Dominic Marner, St Cuthbert: His Life and Cult in Medieval Durham (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000).

[lii] He described Tongareva: “the scene was modern, and the atmosphere throbbed with the spirit of the past” (Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, p. 131).

[liii] Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, p. 168. Later, he was unable to dream of Rapa because he had not been there: “Had it been my fortune to visit Rapa, I might, perchance, have sensed an affinity that personal contact may convey with more subtlety that the written words of others” (Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, p. 184). Umberto Eco likewise evoked “dreaming” of the European Middle Ages as something Americans feel compelled to image and imagine in the absence of a sense of place, or presence—a geographic, temporal, and dare I say spiritual separation and incommensurability that modern historians struggle to overcome. Umberto Eco, Travels in Hyperreality: Essays, trans. William Weaver (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1986), pp. 61-72.

[liv] Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, pp. 270-71.

[lv] Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, p. 291.

[lvi] Epeli Hau‘ofa, “Our Sea of Islands,” reprinted in We are the Ocean, pp. 27-40; and Ingersoll, Waves of Knowing added above. See also Greg Dening, “History ‘in’ the Pacific,” The Contemporary Pacific (Spring/Fall 1989): 134-39; Ben Finney, “The Other One-Third of the Globe,” Journal of World History 5 (1994): 273-97, and Katrina Gulliver, “Finding the Pacific World,” Journal of World History 22 (2011): 83-100. See also Christopher Connery, “Sea Power,” PMLA 125 (2010): 685-92 on the effect of the Pacific on western conception of the sea as a source of power.

[lvii] See, for example, Barry Cunliffe, Europe between the Oceans, 9000 BC-AD 1000 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), p. 419, map 12.9; Fleming, Britain After Rome, throughout shows a distinction between eastern and western Britain in terms of material culture and settlement patterns.

[lviii] See Birgitta Linderoth Wallace, Westward Vikings: The Saga of L’Anse aux Meadows (St. John’s, NL: Historic Sites Association of Newfoundland and Labrador, 2006) and accompanying maps. Only gradually and later were Scandinavians integrated into the southern world of Latin Christendom, ironically due to their own adventurous trade networks and chameleon-like acculturation traits.

[lix] See Samuel M. Kamakau (1815-76), The Ruling Chiefs of Hawaii (1961), rev. ed. (Honolulu: Kamehameha Schools, 1992), pp. 92-104; Te Rangi Hiroa (Sir Peter Buck), “Cook’s Discovery of the Hawaiian Islands,” Report of the Director for 1944, Bishop Museum Bulletin 186 (Honolulu, 1945): 26-43 at 26-30; Gananath Obeyesekere, The Apotheosis of Captain Cook: European Mythmaking in the Pacific (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), pp. 75-77; Marshall Sahlins, How “Natives” Think: About Captain Cook, For Example (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1995), pp. 117, 144; and reviews of the latter two by Greg Dening, Review of Books, William and Mary Quarterly 54 (1977): 253-59 and Clifford Geertz, “Culture War,” New York Review of Books 42.19 (November 30, 1995): 4-6.

[lx] Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, pp. 292-93.

[lxi]Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, pp. 294-95.

[lxii] John Charlot, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Department of Religion, unpublished typescript and personal correspondence. See the Kumulipo, translated by Queen Lili‘uokalani in 1897, at http://www.sacred-texts.com/pac/lku/index.htm

[lxiii] David[a] Malo, Hawaiian Antiquities (Moolelo Hawaii), trans. N. B. Emerson in 1898 (Honolulu: Hawaiian Gazette Co., 1903), chapter 2, pp. 21-22, the translation known to Hiroa/Buck (reprint Bishop Museum Press, c.1951, 1971). See also, Silva, Aloha Betrayed, p. 11 on adaptation of Hawaiian ideas to Euro-American concepts as a form of resistance to colonization.

[lxiv] Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, pp. 248-49.

[lxv] On a sense of “lostness,” see Zvi Ben-Dor Benite, “Modernity: The Sphinx and the Historian,” AHR 116 (2011): 638-52, at 651. On truth-telling narratives, see Jeremy Downes, “Or(e)ality: The Nature of Truth in Oral Settings,” in W. H. F. Nicolaisen, ed. Oral Tradition in the Middle Ages (Binghamton: CEMERS 1995), pp. 129-44. The modern progress myth of magic-religion-science has a long half-life; see n. 17 above.

[lxvi] As a symbol of hope more valuable to him than his degrees and books, Hiroa/Buck kept in his office the canoe paddle given him by his Maori grandmother (technically great aunt) Kapuakore who had instructed him in Maori lore; see http://www.nzedge.com/heroes/buck.html

[lxvii] See Ben Finney, Voyage of Rediscovery: A Cultural Odyssey through Polynesia (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994) and the Polynesian Voyaging Society website at https://hokulea.com/ . More recently, seven canoes sailed to Maui from various Pacific islands: Gary T. Kubota, “Pacific Islanders Sail to Summit in Canoes: the gathering unites indigenous people and scientists to discuss ocean issues,” Star-Advertiser, June 22, 2011 (http://www.staradvertiser.com/news/20110622_Pacific_islanders_sail_to_summit_in_canoes.html); in 2017 Hōkule‘a went on a worldwide voyage and in 2023 is currently circumnavigating the Pacific on the Moaninuiākea voyage for earth.